THE WORLD OF CLASS

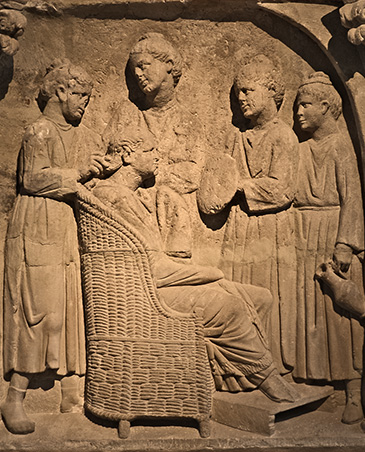

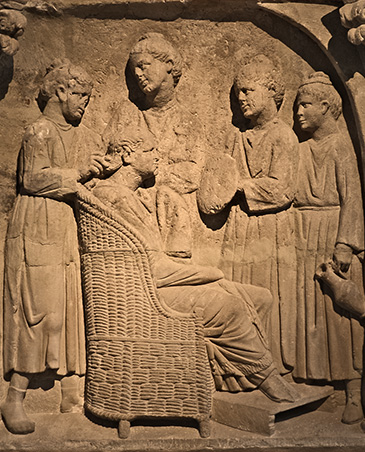

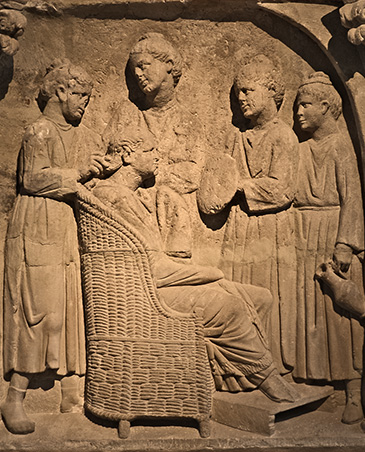

Mistress attended by her slaves

Women experienced class structure both

directly, as it qualified them for certain social privileges and for entry into

the few religious offices open to them, and indirectly, as women's status

derived from males with whom they were most closely associated. From the time

of the kings, Roman citizens (excepting women and children) were registered in

the census by tribe and class, originally for purposes of taxation and military

service; the quinquennial census enrolled new citizens and monitored class

criteria, which had social and political implications for the entire citizen

family. Although the divisions and qualifications of class changed over time,

the hierarchical concept did not, as it translated into wealth, privilege, and

office. An upper-class woman's identity was tied to her social status, as her

single name for much of the Republic was a feminized version of her gens

name, setting the many Claudias, Aemelias, and Julias apart from the crowd. As

sisters, wives, and daughters, elite women shared in the distinction won by

their male kin, jealously guarding their privilege and jockeying for primacy.

They claimed rank through dress, jewelry, public display, patronage, and reputation as

respectable matronae, watching each other carefully for lapses.

Polybius, 2nd century BCE Greek

historian of Rome, describes how Aemilia Tertia, the proud wife of Scipio Africanus, dressed

opulently and rode in an elaborately decorated carriage when she participated

in women's ceremonies; she brought with her sacrificial baskets, cups, and

utensils made of gold or silver and was accompanied by a retinue of servants

larger than any other woman's. She reasoned that such state was fitting for one

who had shared the life of the great general who defeated Hannibal at Zama in 202 BCE (Histories

31.26-27). Epigraphic evidence from the imperial period reveals the names of wealthy women who, perhaps influenced by the example of public benefaction set by the Empress Livia (e.g., Porticus Liviae) and Augustus' sister Octavia (e.g., Porticus Octaviae), gained prestige for themselves through their generosity as civic donors. Because visual and literary sources for the lives of lower-class citizen women and

freedwomen are sparse, it is less clear how class and social distinctions within class

affected their lives. No doubt they were required to work in the house with

little or no help; many also worked outside the home to contribute to family

resources. They, too, must have experienced the benefits and disadvantages of

close community oversight of virtue, family honor, and wealth. For further

information see Hallett (1984), Hemelrijk (1999, 2004, 2015), Perry (2014), Treggiari (2019), Weidemann (1981), Will (1979) in the Bibliography; see also

Images of Class below.

| Text-Commentaries |

Additional Readings |

| Cornelius Tacitus, Annales 15.51, 57: Epicharis |

See the Latin reader

The Worlds of Roman Women for the following

texts: |

Titus Livius,

Ab Urbe Condita 10.23: Pudicitia

Plebeia |

|

| Valerius Maximus,

Factorum et Dictorum Memorabilia 8.3.3:

Hortensia's advocacy |

Petronius Arbiter,

Satyricon 37, 67, 76 (excerpts): Fortunata at dinner |

| Cornelius Nepos,

De Viris Illustribus, Praefatio 2-7:

Greek and Roman women |

C. Nepos, De Viris

Illustribus, frag. 1-2: Cornelia's letters to her son |

| Domitius Ulpianus, Digesta Iustiniani

XXIII.2.43.6-9: social class and prostitution |

M. Tullius Cicero,

Epistulae ad Familiares 14.4, 20: scenes from a Roman marriage |

| Lucius Annaeus Seneca,

De Consolatione ad Helviam 19.4-7:

an aristocratic matrona |

C. Plinius Caecilius

Secundus (minor), Epistulae 8.10: Calpurnia's miscarriage. |

| Cornelius Tacitus, Annales III. 76.1-5: Junia Tertia, wife of Cassius, sister of Brutus |

Gaius, Institutiones

1.144-145, 148-150: tutela. |

Inscriptions |

T. Livius,

Ab Urbe Condita 39.9-10 (excerpts): Hispala Faecenia |

| Funerary for Petronia

Hedone |

C. Sallustius Crispus,

Bellum Catilinae 24-25 (excerpts): Sempronia |

| Memorial for Claudia

Olympias |

Funerary

Inscription for

Naevoleia Tyche, public benefactor of Pompeii. |

| Dedicatory for Eumachia |

T. Livius, Ab Urbe

Condita 1.39, 41 (excerpts): Tanaquil |

| Funerary for Regina Catuvellauna |

See De Feminis Romanis at Diotima for the

following online Latin

texts: |

| Funerary for Antonia Caenis |

Dessau, Inscriptiones

Latinae Selectae |

| Honorary for Cornelia Marullina |

C. Plinius Caecilius

Secundus (minor), Epistulae 7.24: Ummidia Quadratilla |

| Funerary by Septimia Dionisias |

|

| Funerary for Crepereia Innula |

|

| Funerary for the familia Allidia |

|

IMAGES of CLASS

UPPER CLASS WOMEN

- "Pudicitia Pose" of the aristocratic matrona, veiled and posed with her hand beside her face or grasping her palla tightly around her:

- Example 1:

a female statue with a portrait head. Capitoline Museums: Palazzo Nuovo, Rome;

- Example

2: female statue with a fringed cloak (from a Hellenistic type).

Capitoline Museums: Palazzo Nuovo, Rome;

- Example

3: a funerary sculpture from the late Republic or early Empire. Altemps

Museum, Rome;

-

Example 4: marble funerary portrait torso of a mature woman. Augustan age. Vatican Museum: Gregoriano Profano;

- Example

5: a portrait statue in marble of a closely draped matrona of the early Antonine period (side view). 130-50 CE. Rome, Museo

Montemartini.

- Example

6: a funerary or honorary marble statue of a young woman, veiled and modestly draped in expensive clothing (side view). From Turkey. 130-100 BCE. Glasgow, Selingrove Museum.

- Example

7: a limestone funerary relief bust of Haliphat, a fashionable

bejeweled woman of Palmyra's prosperous merchant class who died in 231 CE.

Washington, DC, Smithsonian: Freer-Sackler Gallery.

- Women at Toilette, The fresco shows upper-class women in a room of an elegant house, preparing for a special occasion (a betrothal?). An older woman and a younger look on as a well-dressed attendant arranges the hair of the central young woman. Detail of the facial expressions of the four women. 79 CE. Forum Baths at Herculaneum. Naples, National Archaeological Museum.

- Seated woman elegantly dressed and posed on a bench, holding an apple/pomegranate. This white-painted terracotta figurine reflects the life and tastes of the Greek Hellenistic period that Romans came to admire and emulate. From Tanagra (Boeotia), late 4th century BCE. Copenhagen, Glyptoteck Carlsbad.

- Portrait

head in bronze of a noblewoman; the hairstyle

connects the woman with the late Augustan period. Rome, 14 CE. NY: Metropolitan

Museum of Art.

- Portrait

bust in marble of an upper-class woman, displaying a hairstyle

like that of the Antonine court. Roman. c. 180-200 CE. London: British

Museum.

- Profile

portrait on a sardonyx cameo brooch of an elite woman with a likeness to Agrippina the Elder. Roman, 30-40 CE.

London: British Museum.

- Portrait Bust in marble of a young woman. 3rd century CE. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches

Museum.

- Portrait bust of a woman displaying the hair arrangement of aristocratic women of the Flavian period. Late 1st-2nd century CE.

Rome, Palazzo Nuovo.

- Portrait

in colored mosaic of a stylish woman wearing jewels. From Pompeii, 1st century CE. Naples,

National Archaeological Museum.

- Scene of two formally attired women seated on throne-type chairs in animated conversation; mosaic. Trier, Landesmuseum.

-

Friends: two elegantly dressed women seated on a couch share close conversation; painted terracotta figurine. From Myrina. 100 BCE. London, British

Museum.

- Two women, a younger and an older (daughter and mother?), richly attired, sit quietly but eloquently on a

fragment of a pastel wall fresco. Roman, 1-75 CE. Malibu, Getty Villa.

- Etruscan girl

wearing elaborate jewelry, perhaps molded on real

pieces; life-size terracotta torso. Late 4-early 3rd century BCE. NY: Metropolitan Museum of

Art.

- Seianti

Hanuvia Tlesnasa, elegantly dressed and bejeweled, peers into her mirror on the lid of an opulently decorated sarcophagus. From Poggio Cantarello near Chiusi. Etruscan c. 150-130

BCE. London, British Museum.

- The Toilette: a marble relief of a mistress, seated in

a throne-like wicker chair, having her hair styled by her slaves. Detail from the side of a family tomb monument in Neumagen. Trier, Landesmuseum.

- Isidora: mummy portrait of a woman dressed in costly fabrics and jewels that indicate her wealth and social standing. Her name (Gift of Isis) is written in Greek on one side of her head. Painted linen on wood. Roman, from Egypt, 100-110 CE. Malibu, Getty Villa.

- PATRONAE

- Mineia, a major benefactress of Poseidonia (Paestum) and daughter and widow (her husband was Gaius Cocceius Flaccus) of leading citizens, honored in an unusual way by her local Senate with a small bronze coin (semis). The obverse shows a female head (Mineia? Juno Moneta?) inscribed MINEIA M[arci] F[ilia] (London, British Museum). On the reverse (Berlin, Bode Museum) is an image of a 3-storey

building, probably the basilica in the local forum financed by Mineia; it is inscribed PS [for Poseidonia?] on the left and S[enatus] C[onsulto] (by decree of the Senate) on the right. Minted in Paestum. Late 1st century BCE.

- Volusia Cornelia, a wealthy member of the senatorial class (possibly the daughter of the consul in 56 CE Q. Volusius Saturninus), was a donor to the theater situated between her luxurious family villa and the Sanctuary of Diana at Nemi. This honorary plaque with decorative handles (tabula ansata) was mounted on the frons scenae of the building in gratitude for her restoration of the theater(AE 1932.68). Mid 1st century CE. Rome, Terme Diocleziano.

- Naevoleia Tyche (portrait head in the upper window), a wealthy businesswoman (perhaps freed), built this elegant tomb for herself, her husband, C. Munatius Faustus, an Augustalis, and both of their freedmen and freedwomen. The inscription and accompanying images indicate that the couple was voted by the town council a bisellium (a civic bench for two people) for their benefactions. ILS 6373 (see WRW pp. 134-135; brief video). Herculaneum Gate, Pompeii, 1st Century CE.

- Eumachia held the important public office of priestess and become a

patron of Pompeii's corporation of fullers, the dyers and clothing

cleaners. One of her benefactions was an impressive building, set on

the east side of the

Forum at Pompeii. A side entry contains the marble plaque over the doorway bearing the inscription by Eumachia and her son,

Marcus Numistrius Fronto, dedicating the building to Concordia Augusta and

Pietas (see text). early 1st century CE. Pompeii.

- Fundilia, daughter of C. Fundilius, was the patron of Fundilius Doctus, a mime actor whom she freed. A wealthy woman, she supported a troupe of mimes. Nevertheless, her heavily draped pose and severe expression lay claim to her station as a traditional elite matrona. From the Sanctuary of Diana at Nemi, 1st century CE. Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glypto tek.

- Marcia Aurelia Ceionia Demetrias received an honorary statue (no longer extant) with an inscribed base from the citizens and administrators of Anagnia for restoring the town's baths and re-dedicating them with a public feast and monetary gifts for all. A similar monument was awarded to her father/husband, who made an equivalent separate contribution to this project.

- Civic Donors of Perge and Olympia: Plancia Magna, Aurelia Paulina, Regilla.

FREED & LOWER CLASS WOMEN

- Philematium and her husband Aurelius Hermia, dressed as Roman citizens, appear on a marble funerary relief, one of the earliest tombstones to commemorate the marriage of freedpeople (for the text see WRW, p. 47). From a tomb on Rome's Via Nomentana, c. 80 BCE. London, British Museum.

- Vecilia Hila, freed by a woman of the Vecilius family, is portrayed on a family tombstone with her older citizen husband who wears a toga and is named by filiation and tribe (Lucius Vibius L[uci] f[ilius] [tribu] Tro[mentina]; inscription); between them is a portrait bust of their young freeborn son Lucius Vibius Felicio Felix. Hila is pictured in the draped pudicitia pose of the upperclass matron, wearing the nodus hairstyle of the Empress Livia and displaying the ring of the valid citizen marriage. Named but not pictured is Vibia Prima, the liberta of Lucius, another member of their household (CIL VI.28774). 13 BCE-5 CE. Rome: Vatican Museums (Chiaramonte).

- Old

woman: encaustic mummy portrait reproducing wrinkles and grey hair; the

absence of jewelry and fine clothes suggests she belongs to the lower classes.

Roman, Fayum Egypt, 300-325 CE. London, British Museum.

- Portrait Bust, marble, of an older woman wearing a cap, perhaps a nurse or freedwoman. Second half 1 century BCE. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Drunk:

an African red slipware jug, shaped in the form of a comically drunken old

woman clasping a wine jug. Roman, early third century CE. Boston, Museum of

Fine Arts.

- Maria

Auxesis: marble tombstone with a portrait relief of a freedwoman (see inscription). Trajanic period (98-117 CE). Rome, Baths of Diocletian.

- Caltilia

Moschis, a freedwoman of Ostia; relief detail from her funerary altar.

Santa Monica, Getty Museum.

- Leisure: a painted terracotta mold figurine of two women crouched over a street game of knucklebones. Capua, 340-330 BCE. London, British

Museum.

- Funeral Stele for Dasumia Soteris, set up by her former owner and husband with a moving inscription. (CIL VI.16753) Rome, 2nd century CE. London: British Museum.

- Myrsine with her partner on a marble tombstone; portrait heads in high relief. Inscribed: A[ulus] PINARIVS A[uli] L[ibertus] ANTEROS OPPIA C[aiae] L[iberta] MYRSINE. Mid to late Augustan period. CIL 6.24190. Rome, Altemps Museum.

- Cinerary Chest of carved marble in the shape of a house, with its cover simulating a roof. Inscribed for D. Aemilius Chius and Hortensia Phoebe, freedpersons, this expensive urn would have sat in a niche in a tomb (side with patera, side with urceus). Roman. 1st century CE. CIL 6.11033.

Minneapolis, Institute of Arts.

- Claudia Prepontis, a freedwoman, set up a funerary plaque and an altar (see the World of Marriage) on which she and Tiberius Claudius Dionysius are portrayed as a couple. The plaque is inscribed for her patron (probably her former master and de facto husband) and for her own and their offspring (inscription). 1st Century CE. Rome, Gregoriano Profano, Vatican Museums.

- Grania Faustina, either freeborn or freed, is pictured with her family on an elaborate marble funerary altar set up for them by Papias, a public slave of the Roman people (servus publicus) who is nevertheless dressed in a civic toga. It is inscribed to his contubernalis (partner), the term used instead of coniunx by slaves for whom legal marriage was impossible. 130-140 CE. CIL 6.2365. Rome, Gregoriano Profano, Vatican Museums.

- Hedone dedicated a votive bronze

plaque to the goddess Feronia, worshipped particularly by freedpersons;

inscribed: HEDONE/ M. CRASSI ANCILLA/ FERONIAE V[otum]S[olvit] L[ibens]

M[erito]. Roman, 2nd century CE. London, British Museum.

- Pinnia Didyma, a freedwoman whose columbarium niche was covered by this plaque (CIL 6.7580), dedicated by the freedman Hermes, a friend or her contubernalis (see student project). From the Appian Way. 1st/2nd century CE. British Museum.

- Bennia Helena, a freedwoman and the concubine of P. Valerius Flaccus, dedicated this funerary placque for them both, according to his will. 1st half 1st century CE (AE 1939, 154). Rome, Baths of Diocletian Museum.

- Gaudenia Nicene appears on the front panel relief of the marble sarcophagus commissioned by the freedman wool merchant Titus Aelius Evangelus, for himself and her, only and ever. A freedwoman, she is pictured in a belted short tunic and boots, her hair neatly dressed, holding a funeral garland in her left hand and offering a goblet to Evangelus. The memorial inscription contains her name at the top edge of the relief (FVERIT POST ME ET POST GAVDENIA NICENE VETO ALIVM QVISQVIS HVNC TITVLVM LEGERIT/ MI ET ILLEI FECI); his name is proudly featured below the lectus on which he reclines (T[ITO] AELIO EVANGELO/ HOMINI PATIENTI/ MERVM PROFVNDAT). The pair are surrounded by workmen, animals and tools of the wool trade (see P. J. Holliday, "The Sarcophagus of Titus Aelius Evangelus and Gaudenia Nicene" in The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 21 (1993), pp. 85-100). Roman, 180 CE. Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Cornelia Frontina was the 16 year old daughter of Flavia Nice and Marcus Ulpius Callistus, overseer in the armory of the Ludus Magnus (the school for gladiators), both imperial freedpersons. They dedicated this funerary inscription to their daughter whose name indicates that she had been born into slavery and freed by a member of the gens Cornelia. Found on the Via Appia, 2nd century CE. Rome, Baths of Diocletian museum.

- Sempronia Eune, freedwoman of Gaius, appears on this marble family tombstone, one of the earliest to include a child, with her freedman husband, Quintus Servilius Hilarus and son, Publius Servilius Quinti Filius Globulus, who wears the bulla, the mark of a freeborn male. CIL 6.26410. Rome 30-20 BCE. Vatican Museums: Gregoriano.

- Flavia Athenais and her fellow freedman T. Flavius Genialis dedicated this cinerary niche cover for M. Cocceius Hermadio, their freedmen and women and their posterity (L L P Q E). CIL 6.15904. Rome: Capitoline Museum: Palazzo Nuovo.

- Vibia Drosis dedicated at least three of the four surviving marble monuments associated with her family, probably with money left her by her husband. She set up a stele for herself and her heirs (inscription). She paid for a stele for her former master Gaius Vibius Felix, on one side of which is carved a warning in cursive: Quis/quis/ huic/ moni/mento conti/melia[m]/ non fec/erit dolore[m]/ nul[l]um ex/pericatur. She apparently married Felix after she was freed (note her dedication: patro[no] suo carissimo and her son's name). She dedicated another for her young son, Gaius Vibius Severus (inscription; AE 1992.202-204). The cinerary urn is inscribed for C. Vibius Herostratus and Vibia Haeresis, probably both freed by Gaius and themselves a couple. Rome, Flavian period (69-80 CE). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Gessia Fausta, freedwoman, was presumably the wife of the soldier and citizen Publius Gessius, son of Publius, of the voting tribe of Romilia. She set up this family monument according to the will of the young freedman of Publius, Publius Gessius Primus, apparently their son, both of whom pre-deceased her. Found near Viterbo. 50-20 BCE. ILLRP 503. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.

- Septimia Dionisias, a freedwoman who earned the ius liberorum for bearing four children, set up this marble funerary plaque and erected a tomb for herself, her husband, two of her children, and her freedpersons and their descendants. 3rd century CE. CIL 6.10246. Rome, Palazzo Nuovo (Capitoline Museums).

- Thetis and Charis: dedication on a Luna marble funerary plaque to deceased sisters (Thetis 9 and Charis 15) by their freed parents, Tiberius Claudius Panoptes and Charmosyne. It asks the viewer who does not believe in manes (spirits of the dead) to invoke the spirits of these girls. Panoptes also dedicated the plaque to his fellow freedman Eunus, the girls' tutor/childminder. Above the inscription is a lunette containing two small female portrait busts with Flavian hairstyles, a wreath, and flowers (see photo).

- Cornelia Daphne, a fellow freedwoman and probably his wife, is memorialized on this funerary plaque by Quintus Cornelius Philomusus, a cloak maker, along with four other female relatives and a man, a family which survived slavery together.CIL 6.9868.

All images are courtesy of the

VRoma Project's Image Archive.

Mistress attended by her slaves

Mistress attended by her slaves

Mistress attended by her slaves

Mistress attended by her slaves