Detail from the handle of Roman silver ladle, 2nd-3rd century CE

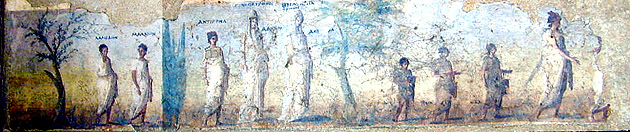

Apart from state religious ceremonies, Roman women took part in private religious observances (sacra). While texts for some of these practices do not survive (e.g. prayers women uttered to Lucina, goddess of childbirth), we have evidence for the role of women in the important family worship of the LAR FAMILIARIS (see excerpts below from Cato, De Agricultura; Plautus, Aulularia; Horace, Carmina; Columella, De Re Rustica; Pseudo-Acro, Ad Horati Saturam; Varro, Apud Nonium; Nonius, De Compendiosa Doctrina; Macrobius, Saturnalia). Women also participated in the rites associated with the LAR COMPITALIS (see excerpts below from Cicero, Epistulae Ad Atticum; Paulus, Excerpta Festi), and in FUNERARY RITES (see excerpts below from Paulus, Excerpta Festi; Paulus, Sententiae; Seneca, Epistulae Morales; Ovid, Fasti) and in religious ceremonies relating to the dead, such as the PARENTALIA (Ovid, Fasti) and the KARISTIA (Ovid, Fasti). In the TERMINALIA (Ovid, Fasti), a festival honoring the god who protected the borders of the family's property, women brought the hearth fire to the altar, much as the woman on the left is doing. For further information about women's roles in ritual, see Panoussi (2019) and Schultz (2006) in the Bibliography.

Bronze Lares and a Lararium, Pompeii 1st century CE

In Women's Religious Activity in the Roman Republic, Celia Schultz points out that since the vilica took over the duties of the absent materfamilias, Cato's discussion of the religious duties of the vilica gives us insight into the religious duties of the materfamilias (see The Worlds of Roman Women, p. 130-131, for Cato's full text of the duties of the vilica).

Focum purum circumversum cotidie, priusquam cubitum eat, habeat. Kal(endis), Idibus, Nonis,

festus dies cum erit, coronam in focum indat, per eosdemque dies lari familiari pro copia supplicet.

Daily worship of the Lares involved not only the dominus and his family, but also the slaves of the familia. While in small households there might be only one altar to the Lares, used by both free and slave residents, larger households generally had two or more shrines. Shrines used by the dominus and his family could be located in the center of the house, while less elaborate shrines used by the slaves were most often located in the kitchen or in peripheral rooms associated with slaves [note]. Normally the paterfamilias led the daily worship of the household Lares, but should he neglect to do so (or be unable to do so), then another family member would perform the rites. In the prologue of Plautus' play, the Lar announces that because Euclio, the master of the household, has neglected to perform the daily worship to the Lar, his daughter has taken the responsibility for this office.

huic filia una est. ea mihi cottidie

aut ture aut vino aut aliqui semper supplicat,

dat mihi coronas.

Horace instructs Phidyle, a farmwife, on the performance of rituals that will honor her household gods to their satisfaction (the meter is Alcaic).

Fresco of Lares and sacrificing Genius (full view), Pompeii mid-1st century CE

Since taking out food stored in the house involved contact with the guardians of the family larder, the Di Penates, and offering such food to the Lares was a religious rite, it was important for those involved in these actions to be ritually pure. Religious purity particularly required that one had been chaste or purified from sexual activity, as Columella explains in this excerpt.

His autem omnibus [scriptoribus] placuit eum, qui rerum harum officium susceperit,

castum esse continentemque oportere, quoniam totum in eo sit,

ne contrectentur pocula vel cibi nisi aut impubi aut certe abstinentissimo rebus veneriis:

quibus si fuerit operatus vel vir vel femina, debere eos flumine aut perenni aqua,

priusquam penora contingant, ablui.

This commentary (a compilation of earlier works by scholars of the 5th-8th century CE attributed to the scholiast Helenius Acron of the 2nd century CE) refers to the rites marking entrance into adulthood for Roman children: the boy assumed the toga pura, putting aside his protective toga praetexta and dedicating his amulet (the bulla) to the Lares familiares; girls at the time of their marriage put away their childhood clothes and dedicated their playthings (see Varro below).

Solebant pueri, postquam pueritiam excedebant, dis Laribus bullas suas consecrare,

Although Varro's work is completely lost, fragments survive in Nonius Marcellus' 4th century CE work De Compendiosa Doctrina; here he lists various items (e.g., chest, doll, ball, hairnet) that girls might dedicate to the Lar upon marriage, their rite of entry into adulthood.

The Lar familiaris and Lares compitales needed to be notified of changes to the family and its household. For example, upon arriving at her new home a bride traditionally offered a copper coin (an as) to her husband's Lar familiaris and Lares compitales (described below), thus informing these deities that she was joining this household.

Nubentes veteri lege Romana asses III, ad maritum venientes,

solebant pervehere, atque unum, quem in manu tenerent, tamquam emendi causa, marito dare;

alium, quem in pede haberent, in foco Larium Familiarium ponere;

tertium, quem in sacciperio condidissent, compito vicinali solere resonare.

The letters of the famous statesman and orator Cicero provide some insight into the daily life of elite women of the late Republic. In this letter he extends an invitation to join his family's celebration of the Compitalia to his best friend T. Pomponius Atticus and Atticus' sister, Pomponia, who was married to Cicero's brother.

This passage is preserved by Paulus from the work of a late 2nd century CE scholar, Sextus Pompeius Festus; De verborum significatu was itself a summary of an etymological work by a scholar of the Augustan period, Verreius Flaccus. It explains that the Lares compitales were in some way connected with the dead. The family hoped that the Compitalia would propitiate the Lares and protect its members in the ensuing year. As women were the wool-workers (lanificae) in the Roman family, spinning and weaving clothing and goods for the household, it is likely that they were responsible for making the woolen balls and effigies to be hung for the Lares.

Pilae et effigies viriles et muliebres ex lana Compitalibus suspendebantur in compitis,

quod hunc diem festum esse deorum inferorum, quos vocant Lares, putarent,

quibus tot pillae, quot capita servorum, tot effigies, quot essent liberi,

ponebantur ut vivis parcerent et essent his pilis et simulacris contenti.

Bringing the corpse to the pyre,

terracotta sarcophagus lid, 3rd century CE

This passage is preserved by Paulus from the work of a late 2nd century CE scholar, Sextus Pompeius Festus, which was itself a summary of an etymological work by the Augustan scholar Verreius Flaccus. Paulus explains the process and rationale for the ritual of purification which featured the elements fire and water.

Aqua et igni tam interdici solet damnatis, quam accipiunt nuptae,

videlicet quia hae duae res humanam vitam maxime continent.

Itaque funus prosecuti redeuntes ignem supergradiebantur aqua aspersi;

quod purgationis genus vocabant suffitionem.

Roman women undertook a period of formal mourning after the funeral of a family member. The duration of this period was determined by the age and relationship of the deceased to the grieving women and the custom changed over time. Paulus describes the length of mourning appropriate to different relationships that was socially acceptable during the middle and late Republic.

Parentes et filii maiores sex annis anno lugeri possunt, minores mense:

maritus decem mensibus et cognati proximioris gradus octo.

deceased woman on a lectus,

Tomb of the Haterii, 1st century CE

the funeral scene; women

mourners,

musicians,

in procession

By the late first century BCE, according to Seneca, only women were expected to engage in formal mourning for any time at all.

Annum feminis ad lugendum constituere maiores,

In the introduction to the month of March in his poem Fasti, Ovid explains why the old Roman year lasted originally only ten months; one explanation relates to the length of time a widow (vidua) was expected to mourn her husband. The meter is elegiac couplet.

funeral Procession to the tomb, end

1st century BCE

priestess with attendants;

wife and family

Ovid describes here the rites to be conducted at the tombs on February 21, the Feralia, the last day for appeasing the dead with gifts from the larder; Ovid warns that it is a day to be avoided by brides for their wedding (557-561). The meter is elegiac couplet.

533Est honor et tumulis, animas placare paternas,

parvaque in exstructas munera ferre pyras.

parva petunt manes.

537tegula porrectis satis est velata coronis

et sparsae fruges parcaque mica salis,

Ovid describes the intent and rites of this festival which took place on February 22. The meter is elegiac couplet.

617Proxima cognati dixere Karistia kari,

et venit ad socios turba propinqua deos.

scilicet a tumulis et qui periere propinquis

620protinus ad vivos ora referre iuvat,

postque tot amissos quicquid de sanguine restat

aspicere et generis dinumerare gradus.

innocui veniant: procul hinc, procul impius esto

frater et in partus mater acerba suos,

625cui pater est vivax, qui matris digerit annos,

quae premit invisam socrus iniqua nurum.

631dis generis date tura boni: Concordia fertur

illa praecipue mitis adesse die;

Ovid explains that the farmer's wife was responsible for bringing the flame from the hearth to start the sacrificial fire and her young daughter was expected to make some of the offerings. The meter is elegiac couplet.

645Ara fit: huc ignem curto fert rustica testo

Sumptum de tepidis ipsa colona focis.

Click on the underlined words for translation aids and commentary, which will appear in a small window.