Slaves on the front left relief panel of a marble sarcophagus for a freeborn child

A slave born of a slave mother in a familia and raised in that household was known as a verna, and was thus distinguished from those slaves who were purchased or inherited. Although the Latin noun is feminine in gender, it was used for both female and male slaves who were born and bred in the domus. The fathers of vernae were likely to be slaves in the familia who were given permission by their owner to engage in sexual union for the purpose of procreating slaves to enlarge the household. Since the master of the domus had the right of complete sexual access to his slaves, it is possible that some vernae were products of such access. Since the distinction between homebred and bought slaves can be found both in literature and inscriptions, it is possible that the Romans considered vernae in a special light, as perhaps more loyal and more trustworthy than purchased slaves. It is certain, however, that when an owner's slaves were called as witnesses or punished in the event of his injury or death, vernae received no special treatment or exemption.

The closer relationship between vernae and their owners and any affection an owner might have had towards a verna depended to a large degree upon association and the size of the household. In large estates, both urban and rural, and in imperial households the number of slaves, whether vernae or not, precluded most from coming into regular contact with the dominus or domina, unless the slaves were personal attendants. In smaller familiae there was more opportunity for contact, which could increase the chances of vernae receiving special treatment, such as being trained in a trade or given the chance to earn their freedom. In the poet Martial's household the death of his vernula Erotion causes him such grief that he writes three poems mouring her loss (Epigrammata 5.34, 5.37, and 10.61) and purchases and maintains a plot where her ashes are buried. Even after manumission, the separate status of vernae in the slave familia is attested by the frequency with which the term appears in funerary inscriptions (see the phrase verna liberta in the inscription for Dorcas below). Yet we know that not all vernae remained in their birth household for the whole of their slave lives; economics, not sentiment, prevailed, as some were sold away for profit and others were included in the dowries of daughters upon marriage. For more information on vernae, see Rawson (in Dasen and Spath) in the Bibliography; she notes that given the high death rate ofchildren, parents might take up their vernae as surrogate sons or daughters or siblings for a surviving child (195). See "Learning to Read Inscriptions," a student activity designed expressly for these texts.

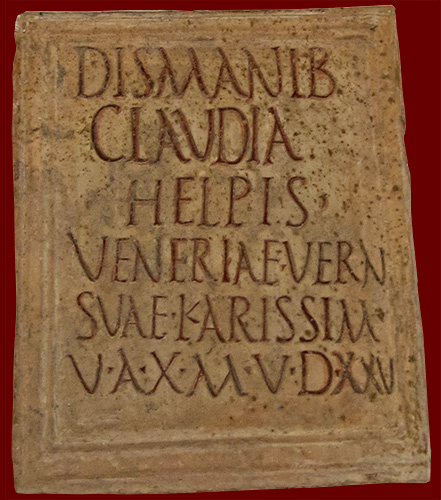

Veneria was a verna, a slave born in the house of Claudia Helpis, who had herself once been a slave and was freed by a member of the gens Claudia (see names of freedpersons). Her mistress's unusual affection for her verna is evidenced by the dedication of this marble funerary tablet with its carved inscription traced in red ink. Households might have several vernae, depending on their size: the poetic epitaph of Caecinnia Bassa mentions at least three other vernae in her family's household (see line 11). While slaveowners did not commonly pay for the burial of their slaves, the poet Martial not only mourned the death of his young verna Erotion in poetry but he paid her funeral expenses (see Epigrammata 5.34), including the fee for her cremation (see Epigrammata 5.37), and secured a burial place for her stone memorial along the Via Appia (see Epigrammata 10.61). Many young Roman slavechildren and children of the poor never received formal burial, but were wrapped in cloth and placed in a shallow pit wherever space could be found, sometimes with a marker. CIL 6.15459.

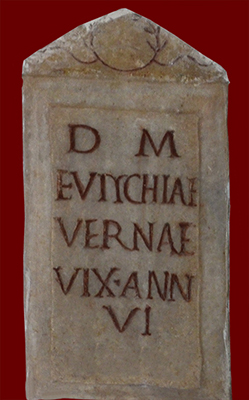

The child Eutychia died at an even earlier age than Veneria (above). There is no mention of a dedicator in the inscription: since her parents were slaves and, if living, were without resources, it is probable that her memorial was provided by Eutychia's master or mistress. The small tablet, its deeply carved letters outlined in red, simulates a tombstone with a pediment containing a line drawing in red ink of a funeral garland, its ribbons curling on either side. The Aurelia Nais monument displays a relief of a funerary garland tied with ribbon of the type that the line drawing attempts to imitate. CIL 6. 17431.

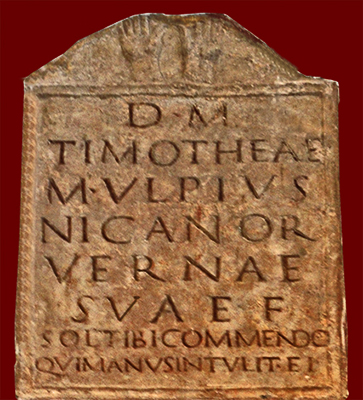

Timothea's plaque, found along the Appian Way, was dedicated by her master, Nicanor, who was a former slave of a member of the gens Ulpia (see names of freedpersons), notable for being the birth family of the Emperor Trajan (98-117 CE). While her age is not mentioned in the inscription, her violent death is. As with Eutychia's tablet, the memorial is shaped like a tombstone, but its pediment contains a relief of a pair of hands, palms out, instead of the familiar funerary wreath. Another example of this symbol of hands raised in prayer or in violence can be found on the funerary tablet for the deceased woman Severa, whose unnamed dedicator implores the god Sol to avenge her unnatural death in similar language that may actually be formulaic. Timothea's owner may have been a devotee of Sol Invictus, patron god of soldiers. The earliest inscriptional evidence of this cult dates to the 2nd century CE, thus perhaps dating this memorial; in 274 CE the cult became official in Rome under the emperor Aurelian. CIL 6.14099

Dorcas was born on the imperial estate of the Emperor Tiberius on the island of Capri and trained to be a personal assistant (ornatrix). As she was freed by Livia, wife of Augustus (see names of freedpersons), Dorcas may well have arranged the hair of the first empress. The pride that Dorcas and Lycastus felt in their service to the imperial house and in their Roman marriage (matrimonium), which was only possible after they had both been manumitted, is revealed in the words chosen for the epitaph. Dorcas is memorialized as a freed verna with a domestic profession; Lycastus, also a freedman of the imperial house and an official (rogator), dedicated the plaque to his legal wife (coniugi). This elegant funerary tablet is deeply inscribed with Augustan style capital letters outlined in red, its inscription framed by a relief carving in the form of a small temple facade whose two Corinthian columns support an empty pediment. (CIL 6.8958).

Stratonice, a verna of the imperial house (Augusti), died in infancy, as did many Roman children of all classes during the classical period, whether from disease or accident. The dedicators were slaves who had Greek names, as did their daughter; possibly they originated in Greece or in a Greek-speaking area of the Empire. They seem to have served in the same household and to have lived with their daughter, for whom they express great affection (dulcissimae). Either because of their position as imperial slaves or because they saved the money to do so, they arranged for their child's burial and dedicated a substantial epitaph for her, which is unusual for slave children. The epitaph presents an anomaly in that the dedicators have male names (Philotechnus and Eutychus), formed from Greek adjectives. It is possible that the stonecutter made a mistake, but since both names have Latin male endings, it is probable that the parentes were indeed men. Both may have been sexually involved with Stratonice's mother, who is not named; she may have died in childbirth, a common occurrence, or at least before Stratonice, whose care was probably given over to a wet nurse. Both men claimed her as their daughter and paid her burial expenses. The monument attests to the family affection that could exist among slaves and illustrates how a slave could negotiate servile status to satisfy the human desire for family. CIL 14.1642.

Alimma is not expressly identified in her funerary inscription as a verna, but it seems to be a safe inference. Her single slave name indicates that she was never freed. She lived to a good age for a Roman woman, most of whom died at a young age in childbirth. She was survived by her father, who was also a slave in the same household; no mother is mentioned, which suggests she had already died. The epitaph contains an unusual statement, that the dominus/a gave his permission -- perhaps as much for the expression of her lifelong dedication as for the memorial itself. Alimma was fortunate to live with her slave father all her life and to have formed a union with a fellow slave; many slaves did not experience such familial stability. ILS 8438.

D[is] M[anibus] S[acris]

ALIMMA QVAE IN VI-

TA SVA SVMMA DISCIPV-

XXXI M[enses] IIII CVI DE PERMISSV

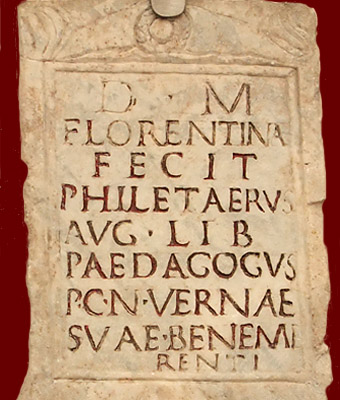

Florentina's stele, found along the Appian Way, was dedicated by her paedagogus Philetaerus, an imperial freedman, probably Greek-speaking, who was the tutor of the children of the emperor's household (undoubtedly the vernae, not the heirs). While Florentina's age is not recorded in the inscription, her teacher's affection for his young charge, who was his own slave or perhaps his daughter (see suae in line 8), is evident: not only did he take responsibility for her burial but he provided her with a decorative monument of marble, a stone to be set free-standing in the ground, and an epitaph skillfully carved by a stonemason with letters filled in with crimson paint, though not well-planned for the available space (see Roman inscriptions). The dating of the monument to the 2nd century places Florentina's death within the period including the reigns of Emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius/Lucius Verus, Commodus, Pertinax and Septimius Severus. CIL 6.7767

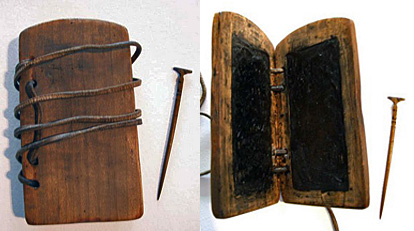

Helene, the home-born slave of Marcus Aurelius Ammonion, resided in Hermopolis Magna, a major city of Roman Egypt. When Helene was 34 years old, she was released from her master’s potestas and given her freedom, for which Ammonion received ample compensation from Aurelius Ales, son of Inarous, of the village of Tisichis, in the nome (district) of Hermopolis. The document clearly states that Ales gave the cost of her manumission to Helene without stipulation, but it doesn't explain why he did so. He may have sought to free her so that they could marry legitimately under Roman law. As Helene was freed by Ammonion with only his friends as witnesses rather than before a magistrate, she would have received Roman citizenship as a Junian Latin, a category of citizenship that was limited but included the right of conubium. The tablets were presumably given over to Helene as legal proof, if she ever needed it, that she was a Roman citizen.

This unique deed of Roman manumission is written on all four sides of two sycamore wood tablets about seven inches high and six inches wide, punched with three holes on the left, bound together and sealed (the seal and fastenings of the diptychon are now lost). The signatures of the witnesses are written sideways on the top half of the front cover (see drawing), while the signatures of the parties involved appear similarly on the back cover. The document is bilingual, written in Roman capitals, the texts only slightly variant: the Latin text is written in the third person, while the Greek text is written in the first person by Ammonion and by Aurelius Ales, Helene's benefactor, who, being illiterate, was represented by Aurelius Ammonius, son of Herminus. The statement of manumission was written twice in both languages, on the outer sides (pages 1,4) with a reed in black ink and on the inner sides (pages 2,3) with a stylus on black wax inlaid in the wood (the ink and wax writing were, even in 1904 when the text was published, too faint to be photographed).

On the border between Upper and Middle Egypt, Hermopolis was called Khmunu by the Egyptians, a center of the worship of Thoth, the patron god of scribes and a god of healing, magic, and wisdom (see history of the site). Because the Greeks identified Thoth with Hermes, they renamed the city Hermopolis during the Ptolemaic period. Its religious significance increased in the 3rd century CE when Thoth/Hermes became an important deity in Neoplatonism. Little remains of the city from the Roman period; the Brooklyn Museum has few artifact fragments from the city's Pharaonic period. For further information on the deed, see De Ricci's articles in the Bibliography. AE 1904.0217.

MARCVS AVREL[iu]S [A]MMONION LV-

PERGV SARAPIONIS EX M[atr]E TERHEVTAE

AB HERMVPOLI M[aio]R[e] ANTIQVA ET SPLEND[ida]

5 ANNORVM CIRCITER X[x]XIIII INTER AMI-

[c]OS MANVMISIT LIBERAMQVE ESSE IVS-

[si]T ET ACCEPIT PR[o] LIBER[t]ATE EIVS AB

AVRELIO ALETIS INAROVTIS A VICO TISICHEOS

NOMI HERMVPOLITV DR[achmas] AVG[ustas] DVA MILLIA

10DVCENTAS QVAS ET IPSE ALES INAROVTIS DO-

NAVIT HELENE LIBERTA[e] SVPRASCRIPTA[e].

ACTVM HERMVPOLI MAIOR[e] ANTIQVA

ET SPLEND[ida] VII KAL[endas] AVGVSTAS GRATO

ET SELEVCO CO[n]S[ulibus] ANNO IIII IMP[eratoris] CAESARIS

15MARCI AVRELI ANTONINI PII FELICIS AVG[usti]

Click on the underlined words for translation aids and commentary, which will appear in a small window. Click on the icon link

![]() to the right of the text for related images and information.

to the right of the text for related images and information.