Priestess presiding over a sacrifice (altar), Sanctuary of Diana at Nemi, c. 200 CE

SACERDOTES: Mamia | Alleia Decimilla | Junia Rustica |

FLAMINICAE: Egnatia Aescennia Procula | Vitellia Rufilla | Julia Helias | Vibia Modesta | Coelia Victoria Potita | Avidia Vitalis | Lucilia Cale| Marcia Pompeiana

The position of priestess (sacerdos) was one of the few socially acceptable public roles a woman could hold. However, the most venerable priestess positions in Rome, the Vestal Virgins (Vestales) and Flaminicae, wives of the flamens, were exclusive to women of elite families. By tradition instituted by King Numa Pompilius (c.717-623 BCE), the sacerdotium of six Vestals each gave thirty years of chaste service to the goddess Vesta, maintaining her sacred fire, cleansing her temple, grinding the sacred flour (mola salsa) for sacrifice to the gods, and guarding the Palladium (see the wooden icon of Pallas Athena on Vesta's shoulder), said to have been carried by Aeneas from Troy and deposited in the Temple of Vesta. Rome's founder Romulus is credited with instituting the first two flamens, of Jupiter and of Mars. Most is known about the wife of the flamen Dialis (priest of Jupiter), who helped her husband in certain rites, wore a special costume, and was subject to several taboos. Her term of office concluded with her own death or that of her husband. During the Republic and under the Empire, within Rome and extra Romam, freeborn women also served as priestesses of several deities (Ceres, Venus, Juno Populonia, Isis, and Magna Mater), while freedwomen and slaves held lower positions as ministrae or magistrae. Following the appointment of Livia in 14 CE as priestess of the cult of deified Augustus, a new category of priestess was added with the title Flaminica Augustae (or with the name of the divinized Empress), which flourished in the provinces if not in Rome.

The costume of priestesses varied according to the deity and, perhaps, the period. One early priestess of the Sanctuary of Diana at Nemi is represented with a high diadem on her head (c. 200-100 BCE), while a later priestess is shown on an altar from the same site wearing a shoulder-length veil over her hair (c. 200 CE). The Vestal Virgins are often depicted with a special headdress composed of a band of wool wrapped several times around the head (infula) with hanging looped or tied side pieces (vittae; see video of recreated hairstyle). However, if the statue of Eumachia, a sacerdos publica of Pompeii, portrays her in her role as priestess, her garments are those of a matrona (stola, tunica, palla), though her palla may have had a purple border, paralleling the toga praetexta worn by magistrates and by provincial priests when presiding over sacrifices. Sacerdotes were often garlanded, as is this Augustan priestess from the Macellum shrine at Pompeii. Flaminicae of the imperial cult probably wore a special headdress like that worn by imperial cult priests, comprised of a golden crown (see Vibia Modesta's dedication) and infula, featuring the busts of emperors and empresses (see also Plancia Magna of Perge). Isaic priestesses had the most distinctive dress; they carried a ritual bucket for Nile water (situla) and a special rattle (sistrum). Usia Prima is shown in her Isaic priestess dress on her tombstone from the Via Appia (40 BCE); Cantinea Procla wears a rearing cobra (uraeus) between 2 stalks of wheat on her veiled head in her funerary portrait (first century CE). A wall painting from Stabiae shows Isaic priestesses of the mid-first century CE in ritual dress, wearing purple tunics, golden breastplates, and a rearing gold cobra on their headbands. Alexandra, Isaic priestess of Athens in the Hadrianic period (early second century CE), wears a mantle tied with the Isaic knot.

The adjective publica (“belonging to the state”) underscores the fact that these priestesses performed rites (sacra) on behalf of the community (pro populo) and at public expense publico sumptu. Women were elected to them annually by the provincial or town council (ordo decurionum). A first century CE inscription from Southern Italy honoring Cantria Longina as both Sacerdos and imperial cult Flaminica (CIL 9.1153) suggests that women elected to sacerdotal office paid a stipend, a summa honoraria, upon entering office, just as magistrates and priests did; the amount of this benefice, which could be quite high, was set by each municipality according to the office. Which deities had a sacerdos publica varied from city to city. Venus and Ceres are the most commonly attested (e.g. Pompeii, Atina, Formiae), but there are other examples, including Liber (Aquino) and Minerva (Bari). A woman could be the public priestess of two divinities at once, as was Alleia, daughter of Alleius Nigidius Maius, public priestess of Venus and Ceres at Pompeii. Election to this office brought a woman into the public eye, both testifying to her high standing in her community and increasing her status. A sacerdos publica of a town, however, need not belong to an elite family: the grandparents of Maius' daughter Alleia were Alleius Nobilis, who was of lowly birth (despite his cognomen), and Pomponia Decarchis, a freedwoman. In rare cases the honor might even be bestowed upon a child of a prominent family, as at Bari, where Petilia Secundina, a girl of nine years, was appointed priestess of Minerva for her special piety. Sacerdotal positions not only gave priestesses social prestige within the city, town or provincial community but also the honor of monuments, both during their lifetime (see Eumachia) and after their death (see Mamia). The priestess of Magna Mater at Ostia in the late second century CE, Metilia Acte, was commemorated as sacerdos Magnae Matris Coloniae Ostiensis on an elaborately carved sarcophagus that she shared with her husband. Sacrifice was the main form of worship of a temple cult. Carried out in public before the temple, sacrifice was a spectacle, often including a procession of sacrificial animals (hostia; victima) bedecked in vittae, accompanied by the utterance of prayers, the pouring of libations, the burning of incense, and the playing of a tibia to drown out ill omens. Less impressive but more common, especially associated with sacrifice by priestesses, was the offering of libations (variously of unmixed wine, honey, oil or milk) or spelt or fruits and cakes (sometimes formed in the shape of a sacrificial animal), and the burning of incense. Through such sacrifices the priestess communicated with the deity on behalf of the community, strengthening divine and social bonds, while those attending gave witness and partook of any remaining sacrificial food.

Mamia (sometimes written Mammia) was a member of an old and prominent Pompeian family. At some point during the late Augustan period (before 14 CE) she was elected sacerdos publica, perhaps a priestess of Venus Pompeiana, the principal tutelary divinity of Pompeii (see Temple of Venus). In this role she followed Eumachia, and, like her, as priestess contributed to the development of Pompeii's civic center, adopting features of Augustan architecture that symbolized the city's accord with imperial Rome. In a gesture typical of the upper classes but impressive at this time for a woman, Mamia assumed the considerable expense of building a temple (#5) on the east side of the Forum of Pompeii, in the area adjoining the building of Eumachia (#7). In the courtyard leading to the temple stands a well-preserved marble altar of the Augustan period: on the front is carved a scene of animal sacrifice before a temple (Mamia's?), perhaps at its dedication; the other three sides are decorated with ritual items and a civic crown. The historic identification of Mamia's temple as the Temple of Vespasian (Sanctuary of the Genius of Augustus), located between the Sacellum Larum Publicorum and the Aedificium Eumachiae, has been much debated. Similarly, a segment of Mamia's dedicatory inscription, carved in Augustan style capitals and assumed to have been set on the temple's architrave, has been questioned. The marble plaque was found broken in several places, notably where the name of the temple deity was incised, leaving only the letters GENI, which have traditionally been resolved as GENI[o Augusti] (see CIL 10.816). Recent scholars, arguing persuasively from wider archaeological, epigraphic and cult evidence, have proposed the alternative resolution below.

In recognition of Mamia's priesthood and doubtless in consideration of her generous benefaction to the city, the decuriones (municipal councilmen) voted her a generous grant of land for her burial, just outside the Porta Herculanensis along the Street of the Tombs (#4). Her funerary monument, probably built by her heirs according to her direction, is in the form of a semi-circular bench (schola) some seventeen feet in diameter, and is constructed of Nocerian tufa blocks; her cinerary urn may have been buried in the ground at the back of the bench. The schola, one of eight discovered in Pompeii and dated between 14-25 CE, was built on a podium a step up from the street and is decorated on either end by a griffin leg. The inscription on the backrest of the bench is deeply incised in oversize Augustan-style capital letters (see opening, middle, end) that extend around the entire bench. A. Mau (1899) writes, “This monument was intended at the same time to do honor to the dead and render service to the living. Here, on feast days of the dead, relatives could gather and partake of a commemorative meal.” The form of her monument guarantees that weary travellers will pause there to rest and, seeing her name, consider the woman whose merits were so highly esteemed by her city.

MAMIA P[ubli] F[ilia] SACERDOTI PUBLICAE LOCUS SEPULTUR[ae] DATUS DECURIONUM DECRETO

Alleia Decimilla served as a public priestess of Ceres (see Livia as Ceres) for the city of Pompeii during the reign of Tiberius (14-37 CE). Public priestesses usually were members of prominent families, and the gens of the Alleii certainly was prominent in the area of Campania. In addition to the impressive cursus honorum of her husband, Marcus Alleius Luccius Libella, who was adopted out of the Luccius family by her father Marcus Alleius, other members of the Alleii held high office in Pompeii (e.g., Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius was quinquennial duovir in 55-56 CE and later Flamen Vespasiani; another Alleia, Maius' daughter, served as priestess of Venus and Ceres toward the end of the reign of the Emperor Nero, 54-68 CE). Alleia Decimilla may have been elected priestess before her marriage to Libella, but more probably after her husband's death, since priestesses of Ceres were to be unmarried during their tenure of office (for this argument, see Schultz, pp. 75-83 in the Bibliography). Since Libella held his highest magistracy, duovir quinquennalis, in 25/26 CE, Alleia Decimilla was probably elected sacerdos publica as a widow not long afterward. The impressive altar tomb she built for her husband and her son stands nearly 15 feet high, on land granted by the city council (ordo decurionum) outside the Porta Herculanensis, between the Street of the Tombs and the Upper Road (Tomb 37). Marble plaques carved with the funerary epitaph below were set under the cornice on the east and south sides of the tomb where they would be visible to those passing by.

M[arco] ALLEIO LVCCIO LIBELLAE PATRI

AEDILI II VIR[o] PRAEFECTO QVINQ[uennali] ET

M[arco] ALLEIO LIBELLAE F[ilio] DECVRIONI VIXIT

ANNIS XVII LOCVS MONVMENTI

PVBLICE DATVS EST. ALLEIA M[arci] F[ilia]

DECIMILLA SACERDOS PVBLICA

CERERIS FACIVNDVM CVRAVIT VIRO

ET FILIO

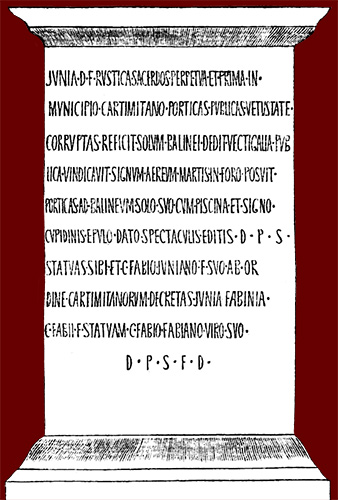

Junia Rustica is distinctive for the level of her benefactions to her community, even in Spain where recognition of female euergetism was highest in the Roman West. She was born into a long-established and politically prominent family in Cartima (near coastal Malaca in Hispania Baetica), a Punic town taken over by the Romans in 195 BCE and given its name. Her father, Decimus Iunius Melinus, was an equestrian in the Galeria tribe, who possibly received Roman citizenship as a local dignitary prior to the Flavian grant to Spain of the ius Latii (the right of commercium et connubium). When she married Gaius Fabius Fabianus, she entered another leading Baetican family noted for its public display of wealth through euergetism so typical of local aristocracies. She herself was honored locally as sacerdos perpetua et prima after her town became a municipium under the Emperor Vespasian (69-79 CE). While towns in Italy and Baetica are known to use the titles sacerdos and flaminica interchangeably, since the text makes no reference to the imperial house, she is listed among the sacerdotes. This honorary inscription, found on her marble statue base and dated to c. 70 CE, celebrates her as a wealthy benefactress of her community. Judging from the repeated phrase D P S (de sua pecunia), her wealth was her own, its use determined by her: the three males in her life, her father, husband and son, are referred to only for purposes of filiation or benefaction. For a discussion of the social and economic implications of her inscription see Donahue (Bibliography).

Marble statue base for Junia Rustica, Cartima, c. 70 CE

F. Carter, Journey from Gibraltar to Malaga II.55 (1777)

CIL 2.1956

IVNIA D[ecimi] F[ilia] RVSTICA, SACERDOS

PERPETVA ET PRIMA IN MVNICIPIO CARTIMITAN[o],

PORTICVS PVBLIC[as] VETVSTATE CORRVPTAS REFECIT, SOLVM

BALINEI DEDIT, VECTIGALIA PVBLICA VINDICAVIT, SIGNVM

[A]EREVM MARTIS IN FORO POSVIT, PORTICVS AD BALINEV[m]

[so]LO SVO CVM PISCINA ET SIGNO CVPIDINIS EPVLO DATO

[et] SPECTACVLIS EDITIS, D[e] P[ecunia] S[ua] D[edit] D[edicavit]; STATVAS SIBI ET C[aio] FABIO

[Iu]NIANO F[ilio] SVO AB ORDINE CARTIMITANORVM DECRET[as

remis]SA IMPENSA, ITEM STATVAM C[aio] FABIO FABIANO VIRO SVO

D[e] P[ecunia] S[ua] F[ecit] D[edicavitque].

Flaminica, the term normally used for the priestess of the cult of the empress/deified empresses outside of Rome, seems to have been used interchangeably with sacerdos in different areas (see Hemelrijk 2005). This cult existed on both the municipal and provincial level, the priestess being elected by the town ordo (sometimes the town assembly also played a role) or by the provincial ordo in the case of a provincial priestess. A first century CE inscription from Southern Italy honoring Cantria Longina as both Sacerdos and imperial cult Flaminica (CIL 9.1153) suggests that these women paid a stipend upon entering office just as magistrates and priests paid a summa honoraria; the amount of this benefice, which could be high (Longina paid 50,000 sesterces, the equivalent of the annual salary in mid-first century CE of some 55 legionaries), varied with each municipality. These priestesses seem to have been selected more frequently from families in the decurial rank than in the equestrian or senatorial class. Since a number of inscriptions note that the priestess’s husband was a priest of the imperial cult, family connections and influence would seem to have played a role in the election of a priestess. However, since the imperial flaminica was expected to provide benefactions to her community during her tenure, wealth and her individual social standing were of great importance. While the government at Rome organized the cult rites to an extent, local towns and municipalities had considerable latitude in choosing which empresses to worship. The imperial flaminicae celebrated the birthdays of the empresses, and perhaps the days of their marriage and birth of their children. In some cases they were attended in public by a single lictor. In addition to presiding over sacrifices, these festal days included games or theatrical performances, as well as public feasting (epula) or distribution of money and food (sportulae), which the priestesses customarily paid for out of their own money. Additional activities that they may have supervised would likely have included the care of shrines or temples, ritual washing, anointing, dressing, and crowning of the cult statues and oversight of the procession of the statues on festal days. Sources on the imperial cult can be found in this Bibliography.

Nothing more is known about the priestess Egnatia Aescennia Procula than what can be learned from her epitaph, carved in handsome Augustan-style capitals on this marble plaque with dovetail handles (tabula ansata), a shape popular for votive and funerary inscriptions among the Romans. It contains her full formal name, including her filiation Publi filia, which thus marked her as a freeborn Roman citizen. In Rome's port city (map) of Ostia, she held the important post of flaminica of the divine Empress Faustina (ca. 100-140 CE). The empress, admired for her beauty and wisdom, was deified at her death by her husband, the Emperor Antoninus Pius, and honored with a temple in the Roman Forum, coins in her image as diva, and the named benefaction Puellae Faustinianae, a program of support (alimenta) for poor orphaned girls. Procula was married to Marcus Modius Successianus, also a freeborn Roman citizen, who survived her.

EGNATIA P[ubli] F[ilia] AESC-

ENNIA PROCVLA FLAMI-

NICA DIVAE FAVSTINAE

HIC SITA EST. M[arcus] MODIVS

M[arci] F[ilius] SVCCESSIANVS

Vitellia Rufilla was a member of one of the four most powerful and influential gentes of Rome in the last half of the first century CE. Her priestly office was a significant one, as Salus Augusta Salviensis was the tutelary goddess of Urbs Salvia (Urbisaglia, in Picenum) and the town's only temple was dedicated to this goddess. She and her husband were members of two related wealthy consular families (he was consul suffectus in 81 CE); they, though active in Rome, maintained a political and philanthropic presence in their home town, where her funerary inscription was found. It was probably the site of their family tomb as well. In Urbs Salvia her husband, Caius Salvius Liberalis, was elected a magistratus quinquennalis (a magistrate in the municipal towns who held his office for five years) for four terms and was voted the distinctive title patronus coloniae as well; their son Vitellianus, who dedicated her epitaph, served as magistratus quinquennalis three times.

V I T E L L I A E

C[ai] F[iliae] RVFILLAE

C[ai] SALVI LIBERALIS CO[n]S[ulis] [uxori]

FLAMINI[cae] SALVTIS AVG[ustae], MATRI

C[aius] SALVIVS VITELLIANVS VIVOS

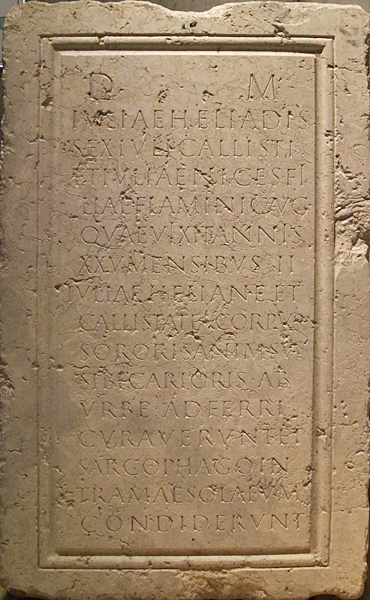

Julia Helias was one of three freeborn daughters of Sextus Julius Callistus and his wife Julia Nice, both former slaves (see names of freedpersons), probably of Greek heritage, who were manumitted by Sextus Julius Helius as confirmed in this inscription. Their former master was a Roman citizen, enrolled in the tribus Palatina, one of the four urban voting tribes at Rome; he was one of the many members of the gens Iulia, a common nomen in the imperial period. Both Callistus and his patron Helius were seviri Augustales in Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon, France), selected as benefactors by the municipal council to superintend the worship of the emperor. Julia Helias’ office as imperial cult priestess (Flaminica Augusta) gave her a position in society that transcended her family’s freedman class. It was further enhanced by being a member of the priesthood in the capital city of the province of Gallia Lugdunensis, the administrative center responsible for maintaining the stability of Gaul (Tres Galliae) under Roman rule. Lugdunum was also the headquarters of the federated sanctuary of the three Gallic provinces (Aquitania, Belgica, Lugdunensis), where in 12 CE Augustus had established the cult altar of Rome and Augustus (see coin of Tiberius minted in Lugdunum), and where Gaul's priestly leaders met annually to celebrate the imperial cult. The inscription is dated to 146 CE, not long after the emperor Hadrian (117-138 CE) completed his reconstruction of Lugdunum, which had been devastated by fire and civil wars (65-69 CE). Julia Helias was still unmarried, apparently predeceased by her parents, when she died away from home; the reasons for her trip, whether related to her priesthood or to family concerns, and for her death at a young age are not mentioned. Her two sisters, Julia Heliane and Julia Callistate, commissioned her well-carved marble tablet and arranged for her burial at home, probably in a tomb together with her parents which may have been owned by the family's patron, Sextus Julius Helius.

Marble monument for Julia Helias, Lyon, 146 CE

CIL 13.2181

IVLIAE HELIADIS,

SEX[ti] IVLI CALLISTI

ET IVLIAE NICES FI-

5LIAE, FLAMINIC[ae] AVG[ustae],

QVAE VIXIT ANNIS

XXV MENSIBUS II.

CALLISTATE, CORPUS

SIBI CARIORIS, AB VRBE ADFERRI

CVRAVERUNT ET

15CONDIDERUNT.

Vibia Modesta was twice awarded the title of flaminica sacerdos by her adopted town Italica (Santiponce, Seville), a colony founded by Scipio Africanus in 206 BCE, in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica. As Modesta twice held the position of flaminica, she may have twice paid the summa honoria, the fee for entering civic office, which is not mentioned here (see Cantria Longina's inscription citing her payment of 50,000 sesterces for her office as sacerdos and flaminica). This inscribed marble pedestal for a statue of Victory dating to the period of Septimius Severus (193-211) records Modesta's opulent gifts to her community, some of which she placed in the Temple of the deified Trajan (called the Trajaneum) where she was the imperial cult priestess. The temple was located in the center of the urbs nova, which was rebuilt and renamed Colonia Aelia Augusta Italica by Trajan's successor, the Emperor Hadrian (117-138), no doubt because the families of both emperors were native to Italica. To give some small idea of her donations, a surviving price list for a silver statue of the Empress Faustina lists its cost at 1,593 sesterces (see valuation); to this figure must be added the expense of the lavish jewelry that once adorned the Victory statue, as well as Modesta's other precious gifts. On line 1 of the inscription the statue dedication is gracefully set off from Vibia's name by a heart-shaped ivy leaf; such hederae distinguentes were used to decoratively separate words in inscriptions from 79 CE on. Because the monument is so damaged (resulting in many variant readings), some details of the text defy translation (punctuation has been added to assist reading). However, the overall meaning of the inscription is comprehensible, and it clearly testifies to Vibia Modesta's wealth, prestige and civic commitment. (AE 2001.1185)

VICT[oriae] AVG[ustae].  VIB[ia] MODESTA, G[ai] Vib[ii] LIBONIS FIL[ia], ORI[unda]

VIB[ia] MODESTA, G[ai] Vib[ii] LIBONIS FIL[ia], ORI[unda]

MAVRETANIA, ITERATO HONORE BIS, FLAMINICA SACERD[os],

STATVAM ARGENTEAM EX ARG[enti] P[ondo] CXXXII [librarum, unciarum duarum, semunciae], CVM INAVRIBUS TRI[bus

mar]GARITIS N[umero] X, ET GE[m]MIS N[umero] XXXX, ET BERULL[is] N[umero] VIII, ET CORON[a] AV[rea]

CVM GEM[m]is N[umero] XXV ET GEMAREIS Z, ACCEP[to] LOC[o] AB SPLENDIS[issimo

or]DIN[e]. IN TEMP[lo] SVO CORONA[m] AVRE[am] FLAMINAL[em], CAPITVL[um] AVRE[um

domi]NA[e] ISIDIS, ALTER[um] CERER[is] CVM MANIB[us] ARG[enteis], ITEM IVNONI[s] R[eginae dono dedit]

Coelia Victoria Potita is the first known imperial flaminica in Cirta, a town in Numidia which Julius Caesar added to the senatorial province of Africa Proconsularis. The text no longer indicates the object dedicated ([sacrum]), but the inscription is carved on what appears to be an epistyle of white marble, now broken into three damaged parts (CIL 8. 19492). The combined status of its dedicator, Quintus Marcius Barea, proconsul of Africa for two terms (41-43 CE), and its wealthy benefactor, Coelia Victoria Potita, the town's first flaminica of the imperial cult, suggests that the dedication was undertaken to bring Cirta to the attention of Rome, particularly the ruling family. While scholars differ as to the identification of the object – a statue, an altar (see Pompeii's Altar to the Genius of Augustus), or a small temple – they agree that it was dedicated to Livia Augusta (30 January 58 BC– 28 September AD 29), the wife of Augustus, as a local response to her deification in 42 CE (commemorative coin) by her grandson, the Emperor Claudius.

Q[uintus] MARCIVS C[ai] F[ilius] BAREA CO[n]s[ul], X[Vvi]R S[acris] F[aciundis], FETIALIS , PRO[consul provinciae Africae] DED[icavit]

COELIA SEX[ti] F[ilia] VI[cto]RIA  POTITA FLAMINICA DI[vae Augustae de sua pe]CVNIA FACIENDVM CVRAVIT

POTITA FLAMINICA DI[vae Augustae de sua pe]CVNIA FACIENDVM CVRAVIT

Avidia Vitalis was awarded the title of flaminica perpetua by the Roman colony of Carthage. Destroyed in 146 BCE at the end of the 3rd Punic War, the site of ancient Carthage remained undeveloped until Julius Caesar in 46-44 BCE Julius Caesar proposed the foundation of Colonia Iulia Karthago in Africa Proconsularis. In 28 BCE Augustus settled 3,000 colonists there, renaming it Colonia Concordia Iulia Karthago. As a result of its good harbor and rich farmland, by the 2nd century CE it had become a flourishing Roman town of over 300,000 inhabitants (see aqueduct, Baths of Antoninus Pius), making it the second largest city after Rome in the West. Although Avidia Vitalis is otherwise unknown, her Roman citizenship is evidenced by her filiation (C[ai]F[iliae]) and her election to the special honor of flaminica perpetua, presumably in the imperial cult. Her benefactions are acknowledged but unidentified, as is the object of her dedication. The inscription (AE 1949.36) is preserved on a fragment of a marble plaque, datable perhaps to the Trajanic period (98-117 CE).

AVIDIAE C[ai] F[iliae] VITALI

FLAMINICAE Perp[etuae] COLONIAE C[oncordiae] I[uliae] K[arthaginis]

CN[aeus] SALVIUS SATVRNINVS

FLAM[en] PERP[etuus]

OB MERITA

Lucilia Cale was a flaminica of the imperial cult of the colony of Thuburnica (Thuburbo Maius, south of Tunis in northern Tunisia). Originally a Punic town that the Romans occupied in 27 BCE as a colony for veterans in the province of Africa Proconsularis, its civic center was built primarily between 150-200 CE. This dedicatory inscription (CIL 8.14690, ILS 4484), once mounted over the entrance to the Temple of Mercury (erected 211-217 CE), credits Lucilia Cale with generously paying its building expenses. The costs of temple construction varied according to the size, location and opulence of its decoration (note the elegantly carved cornice of this Temple of Mercury, located near the Forum); surviving price lists indicate that the smallest temple would cost 3,000 sesterces (see valuation). In line 4 of the inscription Lucilia Cale's name and title are gracefully introduced by a heart-shaped ivy leaf, a hedera distinguens; such decorative markers can be found on epigraphic monuments from 79 CE on.

MERCVRIO SOBRIO, GENIO SESAS[a]e, PANTHEO AVG[usto] SAC[rum].

PRO SALVTE IMP[eratoris] CAES[aris] M[arci] AVRELI SEVERI[i] ANTONINI AVG[usti] PII FELICIS ET

IVLIAE DOMNAE AVG[ustae], MATRIS AVG[usti] ET CASTROR[um] ET SENATUS ET

PATRIAE TOTIVSQVE DOMVS DIVINAE EORVM,  LVCILIA CALE

LVCILIA CALE

FLAM[inica] COL[oniae] THURB[icensis], TEMPLVM A SOLO FECIT LIBENTIQ[ue] ANIMO V[otum] S[olvit].

Marcia Pompeiana was a priestess of the imperial cult in the coastal city of Leptis Minor (Lemta, Tunisia), in Africa Proconsularis. Her filiation (Sexti filiae) indicates that, as a daughter of Sextus Marcius, she was a freeborn woman of the gens Marcia. While her mother's name is not given, the inscription makes note of the fact that Pompeiana came from coastal Caesarea (Chercel, Algeria) with the unusual acknowledgment of her double citizenship (Caesariensi . . . Leptitanae). Even though she was not native to Leptis Minor, having moved there from her hometown some 600 miles away, possibly upon her marriage, her new city awarded her the rare honorific title flaminica perpetua (see Avidia Vitalis of Carthage above). Founded as a Phoenician colony (see history) about the same time as Carthage in the 8th century BCE, Leptis Minor was used as a base by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE before the Battle of Thapsus; under the Empire it was the centre of a prosperous olive-growing district with exports including olive oil and pottery. A statue of Pompeiana once stood on this marble base dedicated by Marcus Caecilius Lurianus and Publius Postumius Marianus, presumably notable citizens who are otherwise unknown. The inscription does not explain what Pompeiana contributed to the city that earned her this esteemed office, although there was sufficient space on her monument to describe her benefactions. Dated to the 2nd century CE, her monument was located in the public forum of the city along with others honoring the city's benefactors, among them that of her prominent husband Marcus Nonius Capito (CIL 8.22903), who is remembered for having filled all the public offices in the city; his monument was dedicated by Marcus Caecilius Lurianus and Publius Postumius Marianus as well.

Marble statue base for Marcia Pompeiana

Leptis Minor, 2nd century CE

(CIL 8.22902)

MARCIAE SEX[ti] F[iliae]

CAESARIENSI M[arci] NO-

NI CAPITONIS, FLA-

MINICAE PERP[etuae], LEP-

M[arcus] CAECILIVS LVRIANVS

ET P[ublius] POSTVMIVS [Mar]IANVS

Click on the underlined words for translation aids and commentary, which will appear in a small window. Click on the icon link

![]() to the right of the text for related images and information.

to the right of the text for related images and information.