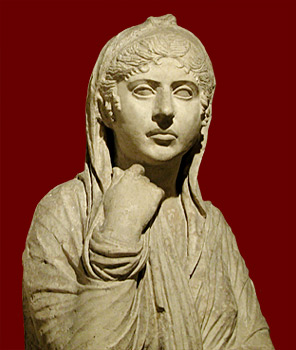

Funerary portrait statue, mid 1st century BCE

Funerary portrait statue, mid 1st century BCE

Cornelia, one of several notable women of the elite gens Cornelia, daughter of Aemilia Lepida and Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio (consul 52 BCE), experienced first-hand the political violence of mid-1st century BCE Rome. Plutarch praises her accomplishments in literature, music, geometry and philosophy, and her freedom from intellectual pretentiousness (Pompey 55). In 55 BCE she married P. Licinius Crassus, younger son of the triumvir, and was widowed two years later when he was killed in Parthia. She became the fifth wife of Gn. Pompeius Magnus in 52 BCE (see Pompey's wives; for Caesar's daughter Julia's death in childbirth in 54 BCE, see pp 94-5 in WRW). Despite the 30-year difference in their ages and the origin of their marriage in political alliance, they were a devoted couple. Cornelia bore him a son, Sextus, and when civil war threatened Pompey sent them both abroad. Cornelia endeared herself to the citizens of Mytilene (Lesbos) to whom she was sent before the battle at Pharsalus. After Pompey's defeat she accompanied him to Egypt and so witnessed his murder by Pharaoh's treachery on September 28, 48 BCE. Reluctantly obeying Pompey's last orders, she escaped, was pardoned by Caesar, and returned to Italy to bury her husband's ashes at his country estate (Pompey 55-80) and relay the message to his son to continue the war as long as a Caesar lived (Lucan, B.C. 9.87-97). Cornelia is one of two prominent women (Cleopatra is the other) in Lucan’s epic. She appears in Books 5 (722-815), 8 (41-158, 577-661) and 9 (55-108, 167-181), portrayed both through Pompey’s doting eyes and, in the tradition of historical narrative, in "her own words." Cornelia's five passionate speeches, delivered at critical moments that underscore Pompey's personal tragedy, reflect audience expectations of virtue in a noble matrona. Doubtless relying on a common source, Lucan and Plutarch both cite Cornelia's piteous self-portrayal as the instrument of Pompey's ruin. Here in her first speech in the Bellum Civile, Cornelia responds to Pompey's announcement that he will send her to Lesbos before the battle at Pharsalus (see scansion of dactylic hexameter and rhetorical terms). For the virtues of Lucan's Cornelia as a Roman wife, see Mulhern's article "Roma(na) Matrona" in Bibliography.