Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita XXXIX: Hispala

Faecenia

Relief of Bacchic masks, 20 BCE-50 CE |

Women are central to the story Livy tells at length in

AUC Book 39, but they remain very much in the background, working

through men who were the public actors in the state effort to outlaw the

"Bacchanalian Conspiracies" in 186 BCE. The cult was supposedly started by a

Greek immigrant in Etruria and quickly spread through Italy. Its secret rites -

night-time celebrations involving both sexes and the use of wine - and rumored

practices - murders, forgeries, and stolen wills - were considered a major

threat to Rome's security. Whether history or legend, Livy's tale illustrates

the interplay of forces that were frequently in opposition in Roman life -

civic and domestic, privileged and voiceless, male and female. Describing the

cult as originally a "woman's religion" (13.8), Livy presents two very different women: the

vicious mother of Publius Aebutius, Duronia, who put her son's life in jeopardy

for the sake of her second husband, Titus Sempronius Rutilus, and Hispala

Faecenia, whom Livy calls scortum nobile libertina, a timid heroine who

reveals the cult secrets first to her lover for his safety and then to the

consul Albinus under threat of punishment. Other women who are credited for

their assistance are: Aebutia, the paternal aunt of Aebutius, proba et

antiqui moris femina (11.5 ), who directs her nephew to report the

conspiracy to the consul; Sulpicia, the consul Albinus' mother-in-law,

nobilis et gravis femina (12.2), who questions Aebutia on behalf of the

consul and assists his interview with Hispala Faecenia; and finally Paculla

Annia, the Campanian priestess responsible for turning the Bacchic rites into

violent orgiastic celebrations with young male initiates.

Chapter 9: Although Livy treats

the episode as a serious threat, the depiction of Hispala Faecenia is

reminiscent of the stereotype of the "golden-hearted courtesan" of New Comedy.

She takes the young Aebutius under her wing, reversing the usual male-female

roles, and, although he is her tutor under law (Gaius,

Institutiones 1.144 ff. ), she proves to

be his protector.

| (5)

Scortum nobile

libertina Hispala Faecenia, non

digna

quaestu, cui

ancillula

adsuerat, etiam postquam

manumissa erat, eodem se

genere

tuebatur. |

| (6)

huic

consuetudo

iuxta

vicinitatem cum Aebutio fuit, minime adulescentis aut

rei

aut famae

damnosa:

ultro enim amatus

appetitusque erat, et

maligne omnia

praebentibus

suis

meretriculae

munificentia

sustinebatur. |

| (7)

quin

eo

processerat consuetudine capta, ut post

patroni mortem, quia in nullius

manu erat,

tutore ab

tribunis et

praetore

petito,

cum

testamentum faceret, unum Aebutium

institueret

heredem. |

Chapter 10: Aebutius tells

Hispala that his mother has pledged his initiation into the Bacchic mysteries

in gratitude for his recovery from an illness. Horrified, Hispala tells him he

would be better off dead; reluctant to accuse his mother of malice toward him,

she insists that his stepfather, who has been the guardian of his estate, is

certainly trying to destroy him. Aebutius' disbelief requires her to explain

how and what she knows about the cult as she begs the gods' forgiveness for

revealing their secrets.

| (5)

Ancillam se ait dominae comitem id

sacrarium

intrasse, liberam numquam eo accessisse. |

| (6)

scire

corruptelarum omnis generis

eam

officinam esse; et iam

biennio

constare

neminem

initiatum ibi maiorem annis viginti. |

| (7)

ut

quisque

introductus sit,

velut victimam

tradi

sacerdotibus. eos

deducere in locum, qui

circumsonet

ululatibus

cantuque

symphoniae et

cymbalorum et

tympanorum

pulsu,

ne

vox quiritantis,

cum

per uim

stuprum inferatur,

exaudiri possit. |

| (8)

orare inde atque

obsecrare, ut eam rem quocumque modo

discuteret nec se

eo

praecipitaret, ubi omnia

infanda

patienda primum, deinde facienda essent. |

| (9) neque ante

dimisit eum, quam fidem dedit adulescens ab his

sacris se

temperaturum. |

Chapter 18: Aebutius reports

the cult to Albinus, the consul, who asks Hispala to give testimony that leads

to the implication of more than seven thousand men and women. The cult

practices were ruthlessly suppressed through a combination of punishments and

decrees enacted in 186 BCE by a shocked Senate, with the approval of the Roman

assembly and under the joint leadership of the consuls Spurius Postumius

Albinus and Quintus Marcius Philippus. Some committed suicide as soon as the

popular assembly approved the Senate's ban. An effective round-up of cult

members followed. Men and women were imprisoned or killed, depending upon the

extent of their participation in the corrupt practices. Men were punished by

the state, women by male relatives who had authority over them. A

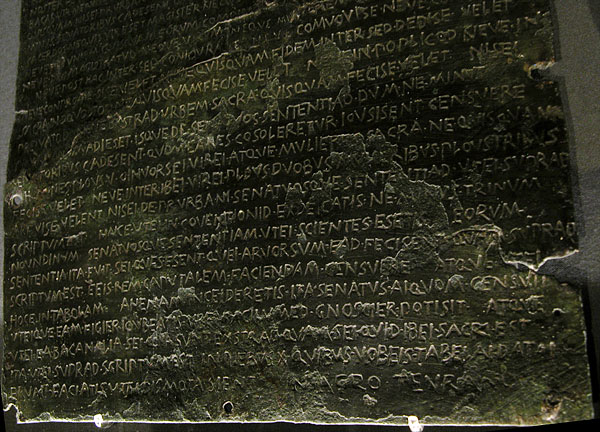

bronze copy of the decree Senatus Consultum de

Bacchanalibus (CIL I.2.581), the oldest

surviving decree of the Roman Senate, was found in Calabria in the 17th

century.

| (6) mulieres

damnatas

cognatis, aut in quorum manu essent, tradebant, ut

ipsi in privato

animadverterent in eas: si nemo erat

idoneus

supplicii

exactor, in publico animadvertebatur. |

Chapter 19: Hispala Faecenia

and Publius Aebutius were rewarded for their service to the state. By decree of

the Senate, confirmed by the popular assembly, each was given an amount of

money equal to the first census class (100,000 copper asses). In addition,

Aebutius was exempted from military service and Hispala was awarded

extraordinary citizen woman privileges that had been closed to her by reason of

her former lifestyle, and received the protection of the

state.

| (5)

utique Faeceniae Hispalae

datio,

deminutio, gentis

enuptio, tutoris

optio

item esset,

quasi

ei

vir testamento dedisset; utique ei

ingenuo

nubere

liceret,

neu

quid

ei

qui eam duxisset ob id

fraudi

ignominiaeve esset; |

| (6) utique consules praetoresque, qui nunc essent

quive postea futuri essent,

curarent, ne quid ei mulieri

iniuriae fieret, utique tuto esset. |

Click on the underlined words for translation aids and

commentary, which will appear in a small window. Close the small window after

each use.

Ann R. Raia and

Judith Lynn Sebesta

Return to

The World of Religion

April 2006