Claudia Piste Inscription: Meter

After the formulaic heading, the epitaph becomes a verse eulogy in

dactylic hexameter (see description in

Reading Latin Poetry). This meter was considered appropriate

for “high” literature, such as epic poetry; thus in Rome it was

associated with the aristocratic classes. Primus must have chosen the meter for

its associations with both serious themes and social status. For a good example

of how a Roman poet played with the heroic significance of dactylic hexameter,

see the opening lines of Ovid's Amores 1.1 in

Intermediate Latin

Readings, particularly the

discussion of the meter.

Inscriptional poems often combine verses of different lengths and do

not always subscribe to the conventions of formal Latin poetry. Most of the

lines of Primus's poem will scan as dactylic hexameter, but there are some

exceptions:

- Line 3 is a line of dactylic pentameter—two and a half metric

feet followed by a strong pause or caesura that coincides with the end

of a word, followed by two and a half feet (see an illustration of this meter

in the elegiac

couplet). The strong metrical break in the middle of the line emphasizes

its meaning—the death of his wife has broken up this “so

well-matched” couple.

- Line 4 will scan only if one treats the ui in debuit

as a diphthong, which may be how it was pronounced

- line5 will scan only if one shortens the long e in

contigerunt, a practice found in poetry

- Line 9 requires that the e in denos be scanned as

short.

Two additional metrical anomalies are very meaningful and allow us to

hear the poet's grief:

1. Line 7 opens like a pentameter, with two and a

half feet followed by a caesura; what follows is a full six feet of

dactylic hexameter. In this way Primus dramatically emphasizes the words nec

vitae nasci, pointing up the tragedy of losing his wife with no new life to

compensate:

2. In line 11, the poet adds two feet in the middle of a pentameter

line, enclosing his name and that of his wife between two caesurae,

vividly calling attention to their union even after her death:

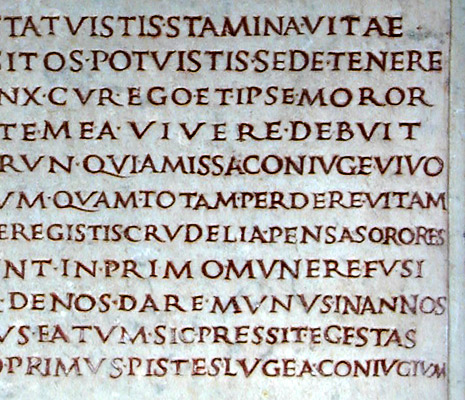

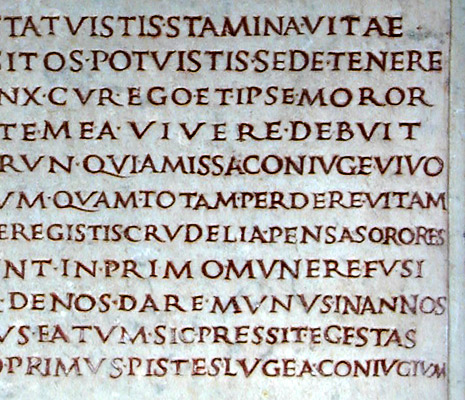

The detail below of the right side of the stone shows the difficulties

that Primus's poem created for the stonecutter: his lengthy poetic expression

apparently caused the stonecutter to decrease the height of the letters in

order to fit the lines in the space. He also had to crowd together letters at

the ends of lines, particularly in lines 7 and 11. This view also reveals what

epigraphers call “interpuncts,” the dots or points frequently used to

separate words in inscriptions, which here are also used to separate syllables

within words longer than two syllables. The blank space below the text may have

been a result of the decreased height of the letters toward the end of the poem

or it may have been intentionally left open for the inscription of a brief

epitaph for Primus upon his death.

Ann R. Raia and

Judith Lynn Sebesta

Return to

Claudia Piste Inscription

March

2006